Mom Rocks

This essay was written in 2020, and revised in Italy at a Yoga & Writing retreat in 2021 (Thank you Jill Filipovic and On the Ground Retreats; read a recent piece of hers for Ms. on what she is reading on Gaza and Israel).

It appeared in Placeletter Substack in 2022 and was revised again from an apartment at Ariane Lotti's beautiful Tenuta San Carlo in 2022.

I imagine this as the intro essay to the book of essays.

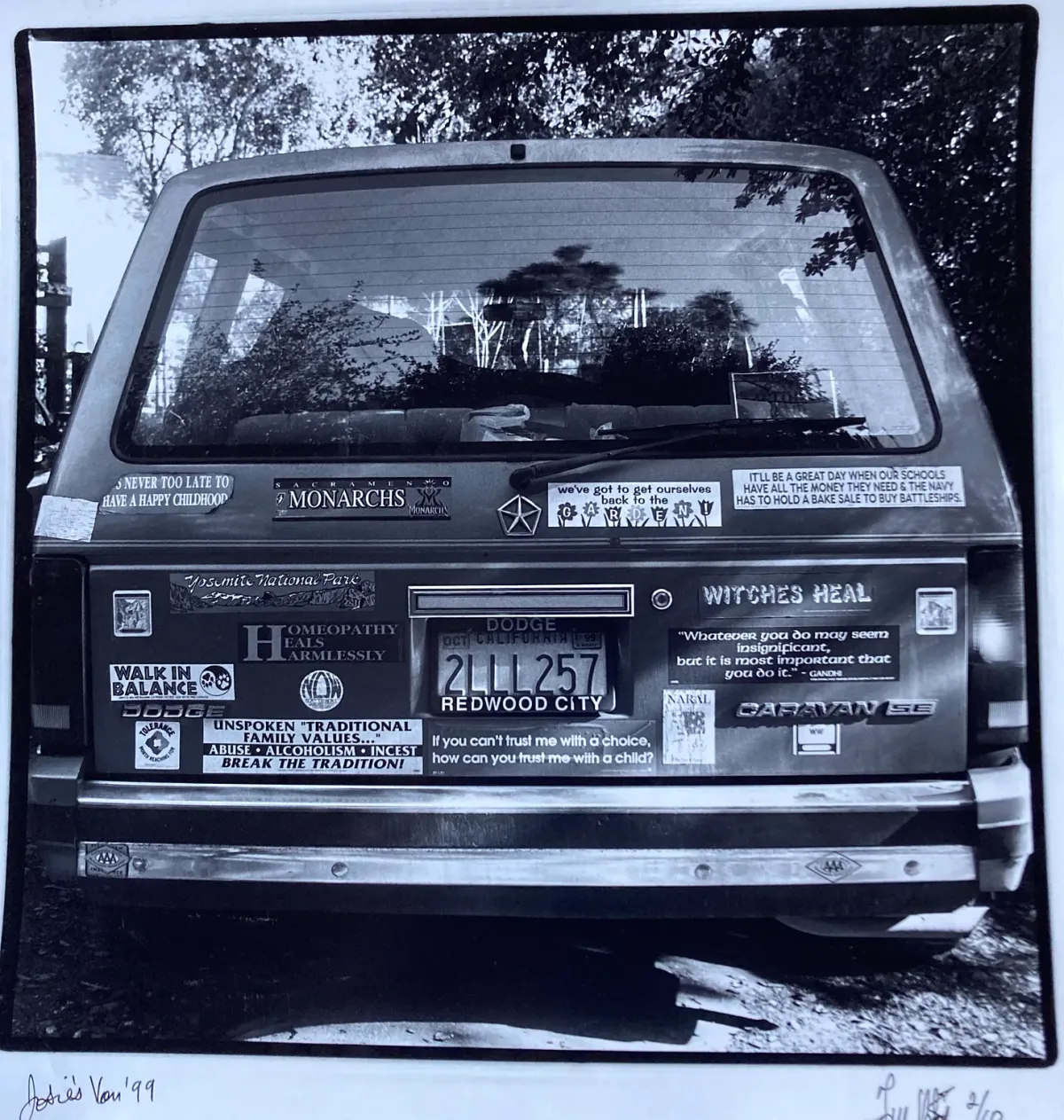

People who know my mom, easily recognize her iconic vans. The first of many I rode in was a VW named Peachy. Peachy was, predictably, a sunset orange shade. She was covered in bumper stickers, a vehicular testament to my mom’s most deeply-held views: “US out of my uterus”, “it will be a great day when the schools have all the money they need and the military needs to have a bakesale to raise money for bombs”, “witches heal”, and “angels protect.”

When I was in third grade, Peachy was replaced by a more modern minivan with a gilded hue called Goldie. By the time I was in high school, the minivan was out and Moonbeam, a Toyota Echo, was my mom’s heart on wheels.

Moonbeam’s dashboard was an altar upon which my mom affixed photos of each of her three children and her granddaughter, all beaming in various states of bliss: a school photo, at the beach, blowing out birthday candles. She accumulated feathers and other found objects from her frequent nature explorations in the front two cup-holders, like a child tucking the remnants of a day’s adventure into pockets.

And Moonbeam’s pièce de résistance: a bright pink sparkly cut-out of the words “MOM ROCKS!”, a gift from my sister.

Sure, it slightly obscured the speedometer, but even on the freeway, mom had to be coaxed to go quickly. “You’re not even going the speed limit,” I’d complain en route to catch a flight. But she always got us there in time, and always left me with the same instructions: “Don’t forget to drink water and take your vitamins.”

Every single time she dropped us off at the airport she would cry. LOVE LOVE is how she ended her emails.

My mother always had snacks in her car, and somewhere to put your trash, and a comfortable bed to lie down on in the back for long road trips. She repurposed an orange Halloween bucket, once used for trick-or-treating, into a portable road toilet.

It was in my own car — a sky blue Toyota Fit named Ocean — that we drove to the coast for the last time. If I had known it would be the last beach trip where she would remember my name, I would have committed each detail to memory. Instead, I take what I recall and blend it into familiar routines from our many beach trips before: We take the winding ride on 84 over the hill, past the place we used to pick olallieberries; we are mostly quiet, unless we’re puncturing the silence by belting out Paul Simon songs, “If you'll be my bodyguard/I can be your long lost pal.” And softly singing Peter, Paul and Mary, “If you miss the train I'm on, you will know that I am gone/You can hear the whistle blow a hundred miles.”

Taking a pilgrimage to Pescadero State Beach is a family ritual. A homing device, or a way to recalibrate. A way to get closer to something larger than ourselves. Something vast and universal.

When I was little, I’d often ask my mother about the story of her youngest sister’s death. “How did Izzy die?” I’d say. She’d repeat the story over and over. Her therapist had told her to tell and retell and tell again — that only then would the impact, the deep grief, begin to lessen.

Izzy’s was the third death in my mother’s immediate family in two years. First was my grandmother from breast cancer. Second was Aunt Francie from leukemia. And then there was Izzy, in a tragic accident after a particularly harsh rain came just as the raft she floated down the Pescadero creek met the ocean.

After Izzy died, my mother sold her first VW van, a blue one, and used the money to buy a backpack and a ticket to India.

After the initial trip, it was a second journey to India in the late 1970s that she met my father. They met at a Gurukula in the foothills of the Nilgiri mountains in Southern India while studying with Guru Nitya Chaitanya Yati — a philosopher, psychologist, author and poet. Eventually returning to the Bay Area. That's when she bought Peachy.

During our last trip to the beach together, my mom scoured the sand for rocks, plucking them out of the wet grit and depositing them into her pockets. By the time we walked back to the car, she had gathered so many that she was physically weighed down, her pants drooping at the sides, her footsteps slowed. My mother was always our family’s keeper of memories. Holding on to so many small things is heavy work.

Now, by telling my mother’s story of how she lived and began the dying process, I too am hoping to lessen my own deep grief.

This book is my attempt to capture the stories, to gently hold each memory like blown glass. It’s an attempt to hold on to my mother as she slowly transitions out of this world.

This is for anyone who knew my mom — a tiny woman, often dressed in purple — and has had the desire to shrink her down and carry her with you in your pocket.

It’s for anyone who needs comfort amid grief, and who wants something stable to hold on to.

It’s a way for me to deal with my own ambiguous sense of loss, my very basic human desire to remember and pass down the things I’ve learned. Among them: To live with joy. To keep and collect. And to drive on in the spirit of my mom, Josie Saracino, someone who truly rocks.